Environmental Works, Inc.’s Investigation/Remediation (I/R) Department handles dozens of contaminated soil cleanups every year. Some of these jobs involve Superfund sites where remediation work is ongoing and can last years, or even decades. Other jobs are smaller and may last several weeks to a month. These projects usually involve the removal of contaminants through excavation or vapor extraction, but sometimes, government entities tasked with providing oversight approve the capping or encapsulation of contaminated soil.

EWI completed construction of such a contaminated soil cap in Kansas City in December 2020 at a Missouri Department of Natural Resources (MDNR) Brownfields/Voluntary Cleanup Program (BVCP) site.

“The Voluntary Cleanup Program is administered by the department’s BVCP Section with the Hazardous Waste Program to provide state oversight for voluntary cleanups of properties contaminated with hazardous substances,” according to MDNR’s website. “Property owners, business operators or prospective buyers want the property cleaned up to standards acceptable to the state, and to receive some type of certification of the cleanup from the department. This certification can greatly reduce the environmental liability associated with such properties.”

Environmental due diligence work on the now-capped site originated with Phase I and Phase II assessments performed by another environmental consultant as part of a real estate transaction between the seller and a potential buyer.

“The Phase I assessment confirmed that the site had originally been used by the adjacent railroad,” Yvonne Huff, Senior Project Manager at EWI and project manager on-site. “And the southwest part of the property was also once a scrap metal yard.”

Understanding the potential for environmental contamination, the previous consulting company conducted a Phase II site assessment.

“The Phase II drilling and sampling was conducted over the whole site and sampling was geared toward whatever use it had served in certain areas. However, only three borings were placed in the central part of the site and only at the edge of where the scrap metal yard had been located,” she said. “Two of the borings did indicate some lead and arsenic contamination, most likely from the scrap metal yard.”

The purchaser was unsatisfied with the results of the Phase II assessment and asked for further investigation to be done. At this point, Nick Godfrey, Principal and National Program Manager-Due Diligence at EWI, connected with both the purchaser and seller.

“Nick got in touch with the client and talked to them about doing a site characterization and enrolling the site in the Brownfields/Voluntary Cleanup Program,” said Huff. “We got involved with this site because the purchaser wanted assurance that the property was safe for use, and part of doing that is getting a certificate of completion through a voluntary cleanup.”

Convinced it was the right move, the seller decided to enter the program.

“(The seller) submitted a work plan to the state, which was approved, to do additional work around the site,” said Huff. “As part of the investigation, EWI came out and collected several soil samples around the two borings with high lead levels that the previous consultant drilled. The investigation that we performed was geared toward the soil samples that we could see from the lab results were above Tier 1 risk-based levels for lead and arsenic.”

EWI worked its way out from the area sampled by the first environmental consultant, sampling a much greater portion of the property.

“We were able to investigate a certain area and expand from there to evaluate the contamination with more borings than just two or three. We drilled eight to 10 borings with three soil samples from each one,” said Huff.

As a result of its investigation, EWI was able to determine that the soil contamination on site was extensive.

“We did that investigation and discovered that there was lead and arsenic in the soil above risk-based levels farther out than we expected them to be,” said Huff. “So, we had to do another investigation. We managed to delineate the area the second time and discovered the contamination covered approximately one acre of the site.”

The investigation did yield one positive, cost-saving result for the property owner – the samples collected by EWI indicated that the contaminated soil started in a layer one foot below ground level. From ground level, there was six inches of existing gravel that covered the lot and an additional six inches of clean soil below the gravel, the two essentially providing a 1-foot cap over the contaminated soil. EWI submitted a remedial action plan to MDNR proposing that the contaminated soil be capped by an additional six-inch layer of compacted gravel on top of the current gravel. Because the existing aggregate was already compacted enough to support heavy traffic, the plan was approved by the state, and EWI got to work on the engineered gravel cap.

According to MDNR’s website, “safe levels of contaminants of concern are based on land use (residential or non-residential) and the analysis of exposure pathways such as direct exposure to surface soil, groundwater use, vapor intrusion into buildings, and others. In some cases, contamination may be left in place with appropriate controls, whether engineering or institutional controls or both, to ensure long-term protection.”

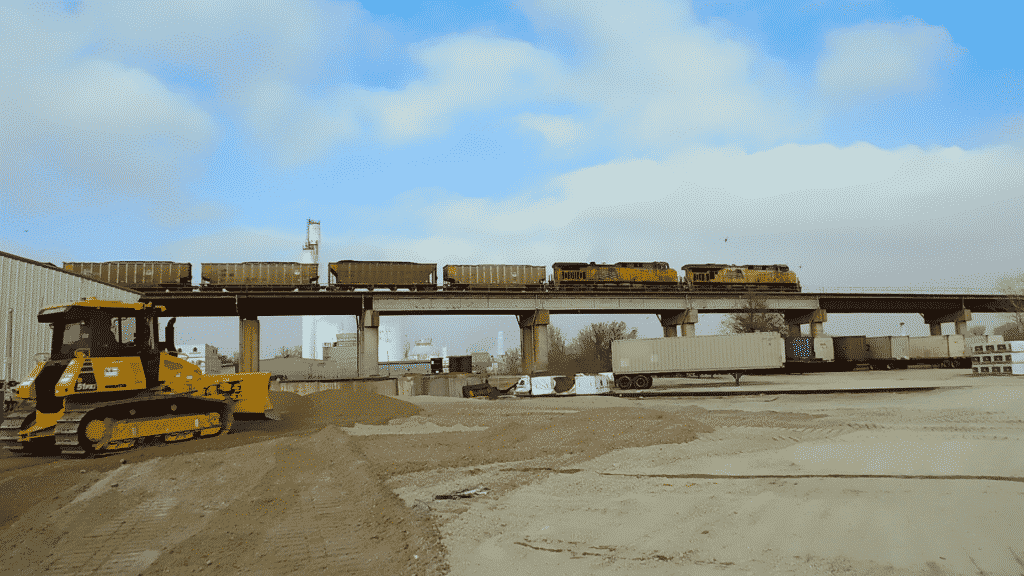

The project was complicated by the presence of railroad tracks running through the property. To make sure that trucks and tractor trailers traveling back and forth across the tracks and throughout the property could do so safely, EWI implemented a slow grade from ground level to each side of the tracks to provide a safe slope and landing.

“We designed a cap that supports the tractor trailer traffic that goes through here. That way these trucks don’t have a hump to go over when they cross the cap to come over the train tracks,” said Huff. “There’s a lot of back-and-forth traffic and heavy equipment that’s on this site.”

Huff said that the seller is relieved that the contaminated soil was approved for capping as opposed to excavation and disposal.

“If the contaminated soil was nearer to the ground surface, we would be either excavating and potentially hauling that off as a hazardous waste or adding one to two feet of cap material, both of which are extremely expensive,” Huff said.

In some cases, capping metals contamination in soils is easier than addressing a number of other volatile organic compounds (VOCs), Huff added.

“Sometimes VOCs are at high enough concentrations the vapors penetrate upward through the soil and could impact people’s health,” Huff said. “Or they may migrate downward to groundwater and flow outward large distances, making cleanup more difficult. Metals tend to stay put, so sometimes it’s easier to provide a sufficient cap to protect people at the surface and metals don’t usually leach to groundwataer as much as other contaminants tend to.”

One downside of capping as opposed to excavating the contaminated soil is that the deed of the property now has a restrictive covenant.

“We had to attach an environmental restrictive covenant to the deed of the property,” said Huff. “The covenant will restrict any construction that might occur below the foot and a half cap. Any construction engineer or anyone on the site doing the excavating will have to understand that below the cap, they’re going to have to deal with soil that is contaminated.